Copyright © 2009 - 2025 Up Helly Aa Committee

Saga of King Harald Olafsson

When King Olaf the Black died in May 1237, he was succeeded by his son, Harald, as King of Mann and the Isles. Harald was based on St Patrick’s Isle, a tidal islet off the west coast of the Isle of Man. Despite its small size, it was by no means insignificant. King Magnus Barelegs of Norway built a castle there during the eleventh century; a highly strategic hub from which his Vikings could rampage, and assert their dominance, far and wide along the northern sea road. As a result, the kingdom that Harald inherited consisted of a widespread archipelago, including Skye and the Outer Hebrides. These were collectively known to the Norse as the Southern Isles (Suðreyjar), quite distinct from the Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland (Norðreyjar).

These were somewhat precarious times for Harald. His neighbours, the Kings of both England and Scotland, were actively eyeing up his realm. Alexander II, the Scottish King, proved particularly menacing. It was no secret that he held a longstanding ambition to annex the isles lying off his west coast. However these Isles were the property of the Norwegian Crown and had been since the reign of Magnus Barelegs. The King of Norway, Haakon Haakonsson, was determined not to relinquish any control over these distant colonies. In fact, he strived to maintain his dominance over them.

Harald was a vassal of King Haakon but had not made any effort to pay homage to his overlord. King Haakon was furious and in 1238 sent agents to the Isle of Man to dethrone him. Harald fled north to the Hebrides while the Norwegians took over his land, not to mention the taxes due to him. Running out of money he tried to invade twice, but on both occasions he was unable to make it ashore and couldn’t replenish his supplies. He had no option but to retreat. Trapped in the isles Harald weighed up his options and realised his only sensible move was to set sail for Norway and submit to King Haakon.

Harald spent two years at the Norwegian Court, during which time he went out of his way to gain the King’s favour. King Haakon was suitably impressed, and graciously restored his title. Harald set out to sea in 1242, stopping first at the Hebrides to assemble a fleet of galleys for the final leg of his journey home. Steering into the harbour at St Patrick’s Isle, it was as if the whole population of the Isle of Man had turned out to celebrate the return of their King. Harald once again established his authority over the isles while managing quite successfully to maintain peace with the neighbouring kings. In 1246 he was issued with papers granting safe passage by King Henry III of England, who on Easter day that same year conferred on him a knighthood. The honour brought Harald prestige, but more importantly it meant he was closer in league with the English Crown. This of course, served to incite Haakon’s jealousy and Harald was summoned to Norway immediately.

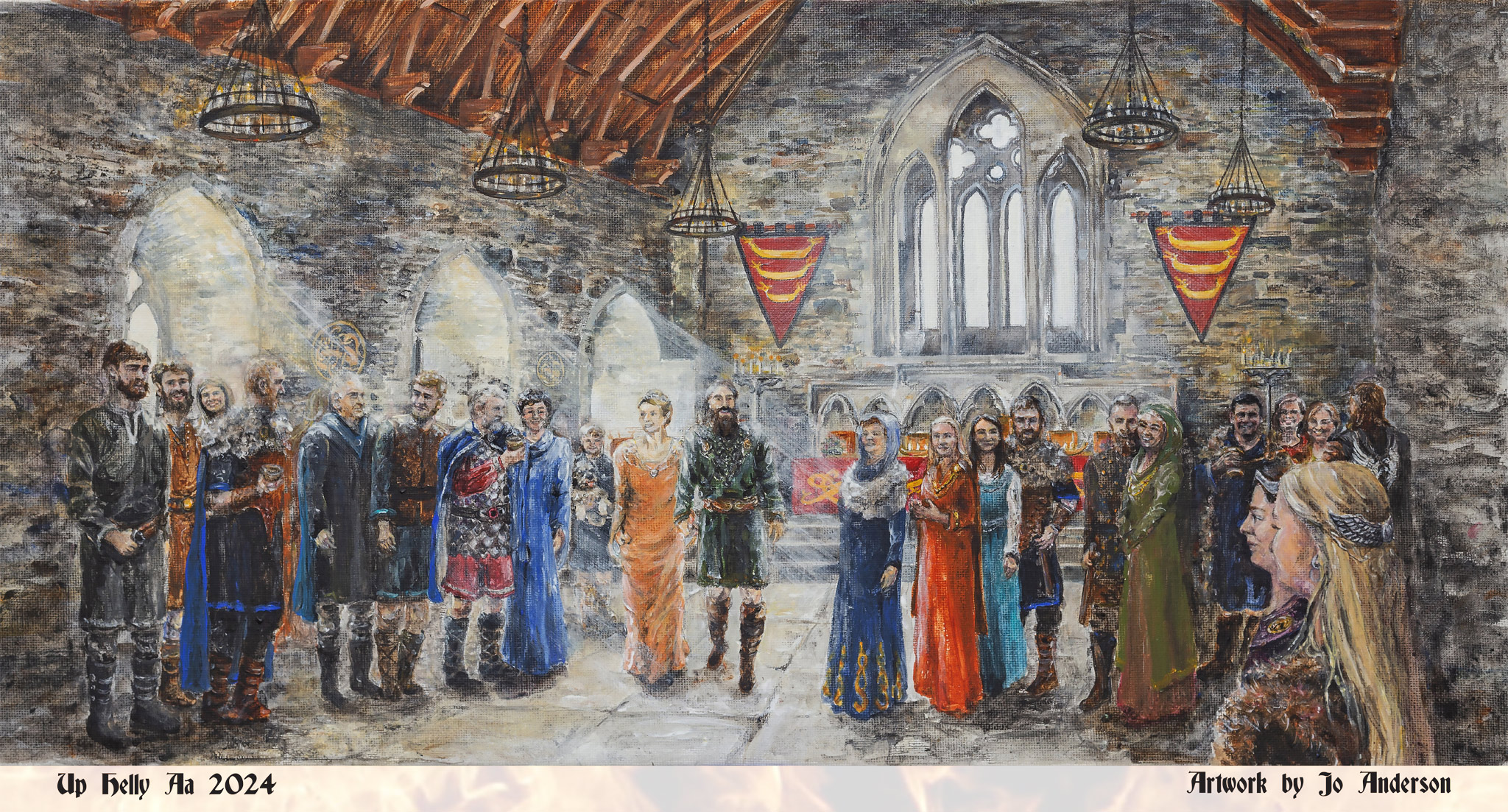

Harald dutifully set sail in the autumn of 1247. He spent that winter with Haakon east in Oslo, and during that time made the acquaintance of Cecilia, the King’s daughter. Harald surmised that such a marriage would win him great kudos. King Haakon also liked the idea as it would cement Harald’s loyalty to the Norwegian Crown, and likewise strengthen his control over the isles to the south. Harald and Cecilia were duly married that following summer in Bergen, and the King hosted a great banquet there at his Royal Hall. (see Collecting Sheet)

After the wedding the couple stayed in Norway two more months before making their journey home to the Isle of Man. During the autumn of 1248, around the feast of St Michael, they set off from Bergen harbour. Harald’s galley snaked its way through a maze of skerries and islets until the sheltered fjord finally gave way to the vast open sea. Heading due west it was plain sailing until their approach to Shetland. A violent storm suddenly blew up. Steering to the south, their ship became trapped in the Sumburgh Roost, a treacherous tidal race, and was mercilessly dashed to pieces in the breaking waves. Wreckage from the vessel was later found strewn over the beaches of Dunrossness, washed ashore from a southerly wind. No survivors were ever found.

In 1930 a bronze ornamental brooch listed in the archaeological records as ‘Viking type’ was found on the beach at Quendale. Its distinctive design has since been dubbed the ‘Quendale Beast’ and bears an uncanny resemblance to the known seal of the realm of King Harald Olafsson of Mann and the Isles.

Brydon Leslie